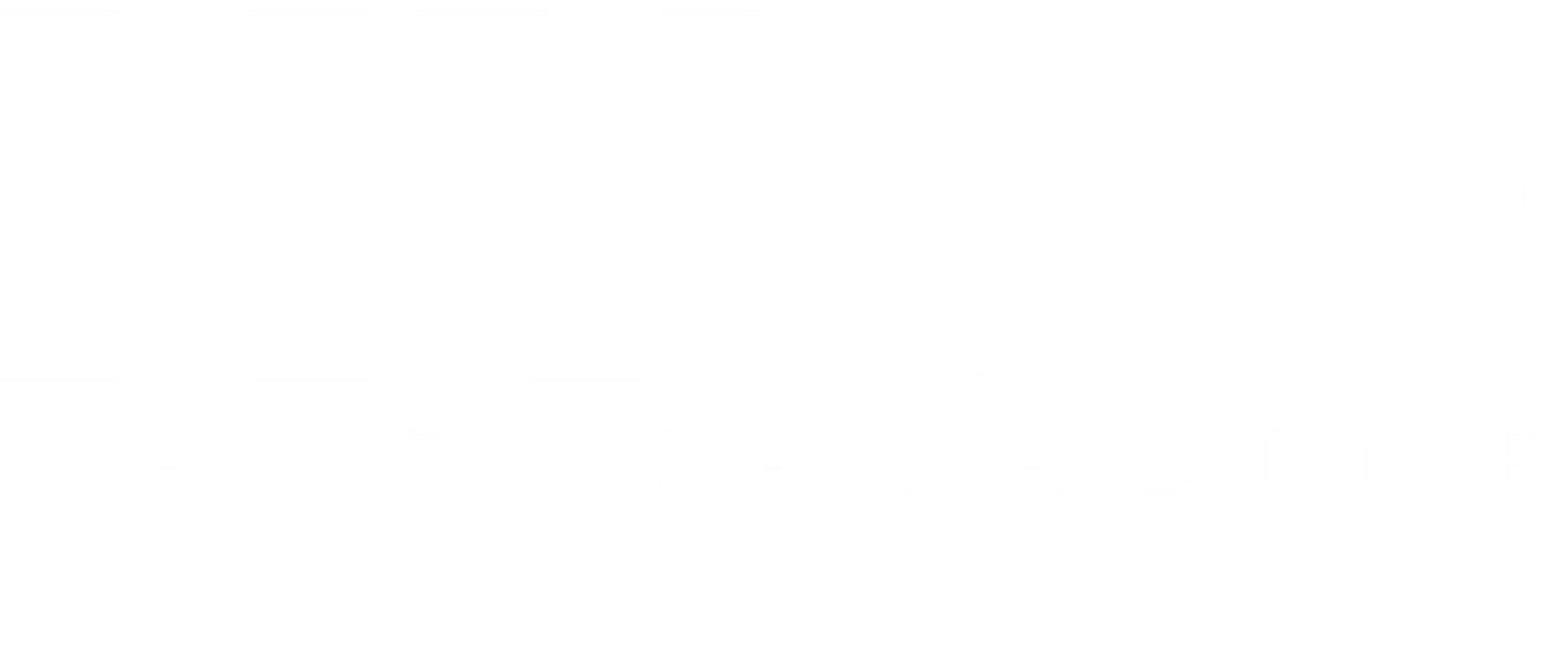

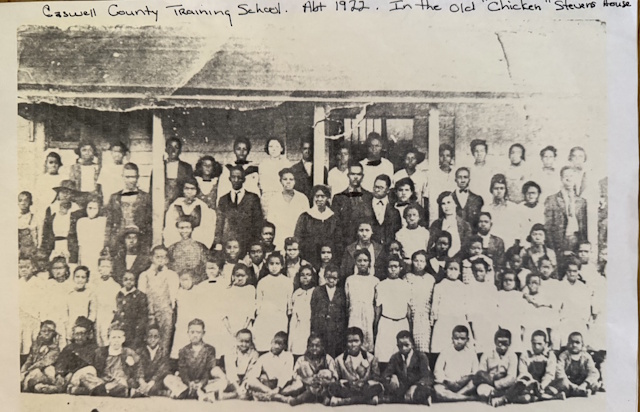

This photo belonged to Karen Williamson’s great aunt, Flora Hughes McDuffie, and was taken around 1935. It shows the students and teachers of one of the Rosenwald Schools in Caswell County, called the Dotmond School. This two-room school in Milton was located along Route 57.

During a dark point in American history, segregation in the rural South was the cause of vast educational inequalities for African Americans. In the 1910s, American educator, Booker T. Washington, and philanthropist and Sears, Roebuck and Company president, Julius Rosenwald, endeavored to improve this. The two worked together to come up with the plans for establishing a fund and architectural plans to establish schools in black communities in the rural South.

The engineering department at Tuskegee University (formerly Tuskegee Institute), where Washington was the founding principal and first president, developed the plans for the buildings that would become the Rosenwald Schools. Rosenwald provided matching grants that paid a portion of the costs, while the state paid another portion. The remainder was paid for by the local communities in which the schools were built through fundraisers, usually in partnership with a local church.

The Rosenwald Fund was born, and from 1912 to 1932, it established more than 5,300 Rosenwald Schools in 15 southern states. In addition to the schools established by this foundation, teacher homes and industrial buildings were also established. These industrial buildings acted as community centers that were a place for the community to learn different trades and participate in workshops. Of these states, North Carolina had the largest number of Rosenwald Schools, with around 853 constructed. These schools were also important to Virginia, with over 380 built during the fund’s existence.

During the time in which they stood, these schools were incredibly important to the communities they served. Today, however, the majority of these Rosenwald Schools are quickly disappearing, and with them, the historical significance they hold. Due to this, the Rosenwald Schools have caught the attention of many groups and organizations dedicated to historical preservation. It is the goal of these groups to preserve these buildings as well as the history they possess.

Pittsylvania County in Virginia had at least 14 Rosenwald Schools, and there are still eight of them standing today, according to the Danville Register & Bee. Those remaining in Pittsylvania County are the Stokesland School, Chatham School, Hurt School, Level Run School, Lipford School, Ramsey School, Shields School, and Sonans School. With 14 schools, Pittsylvania County was one of the leading counties in Virginia regarding Rosenwald School construction. Many of these buildings are still in use today, with some being used as homes. The Stokesland School now houses the Blanks Club, and the Chatham School is currently used as offices for the Danville Pittsylvania County Community Action Agency.

In Caswell County in particular, there have been multiple efforts recently dedicated to educating people about these schools and connecting those that were impacted by them. Out of the hundreds of Rosenwald Schools in North Carolina, Caswell County had six. These were the Beulah School, Blackwell School, Dotmond School, Milton School, New Ephesus School, and the Yanceyville School. Each of them served a different portion of the county, with the Yanceyville School being the largest. None of the original six schools remain standing today.

Director of Caswell Arts, Karen Williamson, grew up listening to stories about her family history, sparking an interest in delving deeper into these stories through genealogy. Williamson said that learning about her family history “helps [her] to have a sense of connection to” her parents, grandparents, great-great-grandparents, “and onward.” Though she grew up in Fairfax, Va., both of her parents were originally from Caswell County; in fact, both attended Rosenwald Schools there.

After learning more about her family’s connection to the Rosenwald Schools and their history in Caswell County, Williamson, alongside her cousin, Ada Williamson James, decided to start the Genealogical Dig program in Caswell County. This was a 10-week program run during the summers of 2018 and 2019 that educated Caswell residents about how to research and preserve their family history. Williamson said, “I feel it is really important to preserve the history, because if not, people are not going to have an appreciation of the place where their ancestors came from.”

This program eventually evolved into Caswell History Speaks, a grassroots organization dedicated to serving Caswell County by collecting, preserving, and sharing stories regarding the history of the county. The current director of this program, Amelia Foster, has focused heavily on the historical preservation of the Rosenwald Schools in Caswell County. The organization held an exhibit titled, “This is my Story, This is my Song,” in October of 2024 at the Gunn Memorial Public Library in Yanceyville that was “an exhibit of artifacts, books, photographs, and documented stories of how the Rosenwald Schools influenced the educational journey of African Americans in Caswell County, North Carolina.”

Foster said, “None of this information is documented, so I am told, so it was a wonderful idea to bring this together, and to talk with people that went to these schools in Caswell County.” Foster collected artifacts and stories from and spent time with Caswell residents who had attended the six Rosenwald Schools. The exhibit also highlighted prominent historical figures in Yanceyville, including Nicholas Longworth Dillard, who was the principal at the Yanceyville School. Many of those at the event who had attended this particular Rosenwald School recounted fond memories of Dillard and his contributions to his community. Many of these stories had not been heard until recently, and due to these preservation efforts, the experiences of many Caswell residents who attended Rosenwald Schools are now recorded. Foster said, “We have to revisit the past in order to go forward with the future.”

There are also many conservation efforts regarding Rosenwald Schools on the state level. North Carolina’s State Historic Preservation Office is currently in the process of doing a county-by-county audit using existing records of Rosenwald Schools to try and locate the sites of schools that are no longer standing. They utilize aerial photography, historic maps, and deed records in order to do so. According to Sarah Woodard, Survey and National Register Branch supervisor in the State Historic Preservation Office, this project has been ongoing for roughly 10 months and has already accomplished surveying and recording Rosenwald Schools in all 25 western counties.

Miranda Clinton is the Rosenwald Schools program coordinator for the North Carolina African American Heritage Commission. She recently hosted an event titled “Celebrating and Connecting: A Convening of North Carolina Rosenwald Schools.” This brought together historic preservationists, local stewards of Rosenwald Schools, and people who attended Rosenwald Schools themselves to encourage continued preservation of these schools. Clinton believes the legacy of the Rosenwald Schools to be “living history,” as many people who attended Rosenwald Schools are still living and sharing their stories today. According to Clinton, “It was not just an effort by the Rosenwald Fund, but an effort with Booker T. Washington and with the communities as a whole.”

The Rosenwald Fund stopped operating shortly before the integration and desegregation of schools, as more educational opportunities became available. Clinton said, “This history is significant to showing how, in a time period where education was not easily accessible, especially for rural African Americans, this was how they were able to get educated.” The Rosenwald Fund was an important early step for improving educational equality. The historical preservation of the Rosenwald Schools is important to many people because it means preserving the stories, history, and impact that these schools had in the South.

Clinton said, “This history speaks to the significance of African American history and African American education history within the state, and speaks to how preserving this history helps to preserve and understand where we have come in our educational history as a state.”