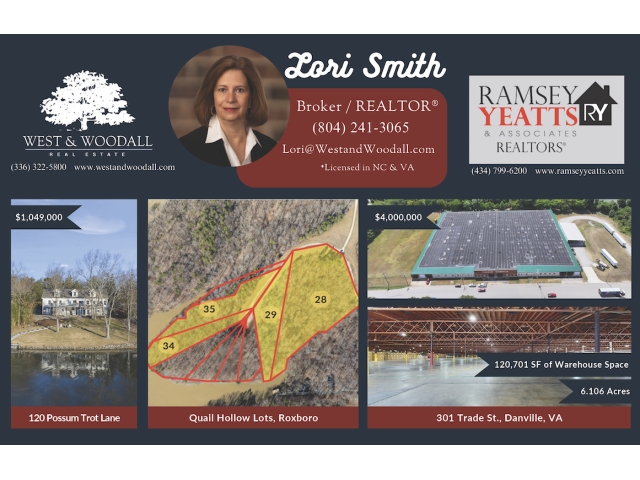

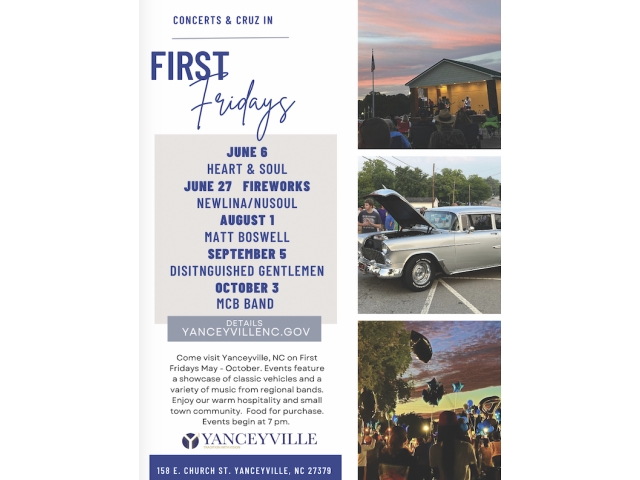

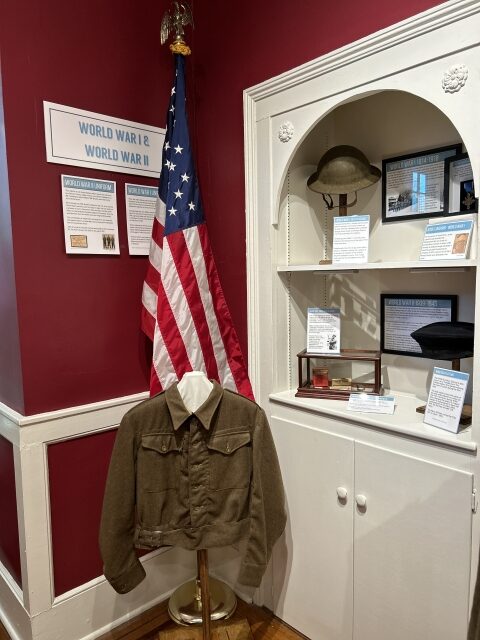

Bill Bowles wore this short jacket when he was liberated from a prisoner-of-war camp during World War II. It is part of the permanent collection of the museum.

On Dec. 7, 1941, radios all over Person County were alerting Americans that they were under attack. The Japanese military had bombed Pearl Harbor. In a Timberlake farmhouse, Vic Bowles was home on leave from military service. Many years later, his sister Mary would recall that moment, “When they came on the radio saying that Pearl Harbor had been bombed and the first announcement was that all military personnel should report to base. He [Vic] got his stuff together and he had a ride back to base within [an] hour, hour and a half.”

Vic and his brother, Bill, were both already serving in the military when the United States officially joined the fighting in World War II. Their parents and their younger sister, Mary, would remain on the home front, like many other Personians, waiting anxiously for word from their boys overseas.

The Bowles siblings were children of the Great Depression. They grew up on a farm that provided most of their basic needs, with the family only purchasing a few staples like flour, sugar, and oatmeal. During the lean years, Bill and Vic would shoot rabbits and sell them at the local store. Instead of cash, they received a “due bill” which was the equivalent of store credit. Bill remembered trying to trade the due bill with his father for real money that could be used in town, but even if he couldn’t, “you could buy quite a bit of stuff at the little country store.”

In 1944, Bill was taken as a prisoner of war by the German forces. He was held in a camp guarded by older men, some in their 80s. They were not abused, but it was not a pleasant place to be. “We started to volunteer some to go out to town to clean off floors and things in order to get out and see if we could get some food,” he shared. “See, basically what food we got in those camps was rutabagas and … we’d make soup out of it with nothing else in it.” He and others in the camp didn’t use this time outside to try and escape because they had no idea where they were and didn’t know where any troops might be, either friend or foe.

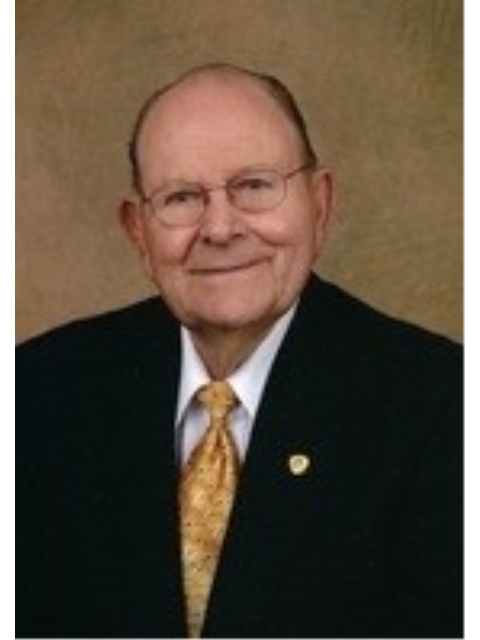

Faced with captivity, watching others get sick and die of starvation or dysentery because they didn’t have access to a clean water source, one would think the nearly five months as a prisoner of war would have been filled with fear. But when Bill was asked if he was scared, he replied, “Not really, you get to a place where you might as well go today as tomorrow and that’s the sort of attitude you got.”

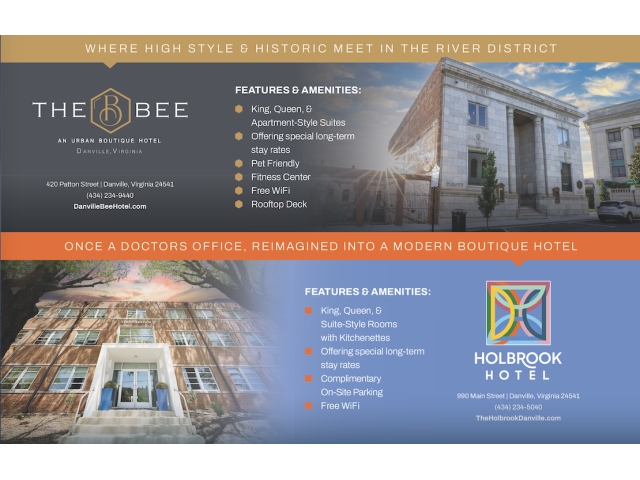

William “Bill” Bowles did not die during World War II. In fact, he lived to the ripe old age of 100. He entered service weighing about 180 pounds. He left Europe weighing 90 pounds. His sister Mary recalls that they brought the prisoners of war home on a “slow boat” so they could fatten them up. Bill came home in a British uniform; after his weight loss and months in the camp, his uniform was no longer suitable. This British uniform he wore home is now part of the collection at the Person County Museum of History.

The stories of Bill, Mary, and their brother Vic, who also survived the war, are priceless. They are a frozen moment in time, a way to understand the world that came before and shaped the world we have today. Mary’s daughter, Debbie Leonard Parker, recorded an interview with her mom and uncle in April 2009 for StoryCorps. In doing so, she preserved this history for not just her family, but for everyone else as well. Reading their experiences is impactful. Listening to them tell their stories, complete with the normal pauses in conversation, as well as their unique accents and inflections, will give you chills.

The tradition of storytelling to share our histories has been around as long as there have been humans, but as an American academic discipline it has a more recent history. As recording technology evolved in the early 20th century, historians and researchers began to use these new methods to record individuals sharing their own stories. This practice was bolstered by New Deal era programs including the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) which both focused heavily on folklore and recording the histories of formerly enslaved individuals.

In 1948, the first academic program for oral history was established by Alan Nevins at Columbia University in New York. Oral history as a discipline is recognized at academic institutions and communities all over the world. Here in North Carolina, there are numerous repositories of oral history, from the State Archives in Raleigh to the Southern Oral History Project at UNC-Chapel Hill to the Community Voices project at the Person County Museum of History.

Established in 2023, Community Voices was created to capture the unique stories of the people who call Person County home. Funded by a grant from NC Humanities, (nchumanities.org) the project focuses on collecting oral histories, transcribing them, and making the stories available to the public free of charge through a partnership with the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center (digitalnc.org).

Born in 1953, Roxie Ramsey Russell experienced desegregation in Person County first-hand. Her father was the first African American sheriff’s deputy in the county, and she attended both segregated and desegregated schools. Roxie’s story joins the stories of Cleo Talley Umstead, age 103, who shares memories of the past in a gentle voice.

There are also the recollections of Carl Lawrence, a veteran of Korea and Vietnam, who shares his experience, in his distinctive southern drawl, of the not-so-happy return of service members from the divisive Vietnam conflict. Though they are different people, they share the commonality of calling Person County home, and their stories have value, especially because they are the ones telling them.

To date, the project has emphasized collecting the stories of individuals whose long history in our community and first-hand experience of important historical events is in jeopardy of being lost, including those who served in the military. The museum is also actively gathering oral histories from those who have typically been underrepresented such as African Americans and Native Americans.

While the grant-funded portion of the Community Voices project is slated to wrap up by the end of 2024, the collection of oral histories will not stop for the museum. These stories are too important, often providing the context that is missing from written histories. If you or someone you know would like to participate in the project, either as an interview subject or an interviewer, you are encouraged to visit the museum website to learn more.

320 East 9th Street

Suite 414

Charlotte, NC 28202

(704) 687-1520

NCHumanities.org

309 N. Main Street

Roxboro, NC 27573

(336) 597-2884

personcountymuseumofhistory@gmail.com

PCMuseumNC.org/community-voices